Getting a Job in CG: Real Advice from Reel People, Chapter 3: What to Learn. By Sybex

Getting a Job in CG: Real Advice from Reel People, Chapter 3: What to Learn

This book excerpt is from "Getting a Job in CG: Real Advice from Reel People" ISBN 0-7821-4257-5. All rights reserved. Chapter 3: What to Learn., is posted with permission from Sybex.

Knowing the job descriptions in 3D and effects described in the first two chapters can help you find the kind of job that fits your skills and interests. Perusing the descriptions and sample listings, you might have realized that there are skills you lack.

This chapter explains the skills involved in 3D and effects and gives you direction on how to acquire them. We first discuss the groundwork of an arts education, then move on to highly technical, engineering-type skills, and then describe specific 3D skills—in particular, using Maya—that you’ll need for any of the jobs where 3D is the major focus of your work.

- Core art and technical skills

- 3D-specific skills

- Other skillsFundamental Skills

The first thing you must accept about 3D design, graphics, and effects is that it’s an art form. The ultimate product of your work will be images, film, or interactive media, made to inform, entertain, or move the emotions of an audience of hundreds, thousands, or millions of viewers. The second thing you must accept about 3D is that it involves many highly technical skills and aptitudes tied to the bane and benefactor of the modern commercial artist’s existence: the computer. It is these fundamental characteristics of 3D that attract and hold a special kind of person: the tinkerer with a good eye, the visual storyteller with a gift for spatial complexity, the inventor with a keen sense of line and color. 3D design appeals to the same people who might have been cathedral architects or bridge builders in another time, and some of these people are Leonardo da Vincis of the twenty-first century.

Does that mean everyone doing 3D is a Renaissance genius? Alas, hardly. But, to be truly good at 3D, you have to see with your right brain while still moving fluidly in the left-brained world of the digital medium. Some people are better at this than others.

| Can’t tell your left brain from your right brain? According to Dr. Betty Edwards, author of perennial bestseller The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, the mind is split down the middle functionally, as well as literally. The right side is the part that’s good at seeing and communicating visually. The left brain, which often dominates, is all business and is preoccupied with processing the verbal and symbolic information that’s so prevalent in the use of computers. Because our left brains dominate our daily life, they also tend to control how we draw, resulting in symbolic rather than realistic representations of what we see. Edwards’ fascinating, practical book provides exercises to help you learn to switch from left-brain mode to right-brain mode, more or less on demand. It’s a great book for 3D artists who have to make this switch all day long. |

Undoubtedly, the best way to learn to see with your right brain and still function with your left is to spend a considerable amount of time doing both. For students, that means getting a thorough education in visual arts, with a liberal dose of computer skills thrown into the mix. Listen to Brian Freisinger, lead 3D modeler at ESC Entertainment, who built many of the digital humans, props, and sets for The Matrix movies:

I hear people bitch when they go to art school, “I’m not going to take drawing classes; I’m going to be on the computer.” But it’s those core fundamentals, basic design skills—you know what, the software changes, the pipeline changes; everything changes, but your core skills, that’s what you build off of. If you built your career on being an expert in this one software package, and all its ins and outs, what happens if that software company goes out of business next year, and the next thing you know, you’ve got to start again. But not if you have this core of understanding things, you spread yourself out a little bit.

You don’t have to be a programmer, but take a Perl class, or read a book. Take a drawing class, or read a book. Be broad-based in the fundamentals. When you understand the principle concepts of how something works—like on the core level, how design works and composition works and how things are put together—for modeling, that’s the basis of it. And for software, if you just understand the basics of how the software works, you don’t have to understand everything, not how to program it, just the basics, you can pick the other stuff up very quick because you know what you’re looking for.

—BRIAN FREISINGER

Brian is one of many artists interviewed who repeatedly emphasized that the most important part of preparing for a job in 3D is to master the fundamentals of art.

Art Fundamentals

A basic education in fine art includes courses in art history, film history, drawing, painting, sculpture, architecture, and photography. More specialized areas of instruction include graphic design, storyboarding, character design, character animation, and cinematography. Although all of these studies are valuable and teach skills that will stay with you throughout an art career, many artists get only a fraction of this scope in their education. What they all get, if they’re going to have a prayer of success, is an understanding of the fundamental aspects of art: line, color, composition, form, and proportion.

Drawing

Drawing is a fundamental skill for many 3D artists, especially at the concept art stage. Concept artists in games and film draw characters, props, and environments for nearly every element that makes it into production. Environment artists produce working drawings of their levels before they start working on 3D models. Character artists produce drawings of characters in multiple poses, with many different expressions, before modelers take on the task of molding the character into 3D. Many managers cite a preference for hiring professional illustrators who are not only good at communicating design internally, but who can produce the fine-looking artwork that sells a project or concept to clients. The theory goes that if an artist can conceptualize and then actualize in drawings, they will take to CG much easier than those not experienced with drawing.

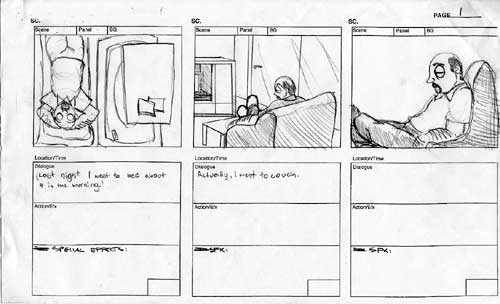

Figure 3.1 Storyboards sets the tone and plan for a production and are important to the overall production as well as to the creative process.

Storyboarding

Storyboard artists produce comic book-style drawings to plot out the elements of a shot or a scene. Storyboards can range from very simplistic barely-better-than-stick-figure drawings that simply block out action, elements, and camera moves in a sequence to highly stylized artwork that gives a strong impression of key emotional changes and poses that a character will go through (see Figure 3.1). Storyboards are a dead giveaway that you’re in a real-live animation studio.

Painting

Painting is even a more common requirement than drawing in 3D art departments. Concept artists paint characters and scenery to develop color schemes and set the tone for visual environments. In games, the job description for 3D artist includes painting textures, which are used on nearly every surface. Texture painting involves manipulation of photographic images such as car wheels, stone walls, or concrete, as well as painting realistic surfaces from scratch. In film work, texture painting is usually relegated to a separate department, and texture painters sometimes overlap with matte painters, who are artists skilled in painting the believable but not necessarily realistic stylized backgrounds used in many film shots. 3D painters need a good sense of color and texture and an intuitive understanding of how light interacts with surfaces (see Figure 3.2). Emmanuel Shiu, a matte artist at The Orphanage, a fast-growing effects studio in San Francisco started by former Industrial Light and Magic employees, talks about one niche for painters.

Matte painters are very much of a niche market, and to do that, you basically have to have strong painting skills, you need to be able to make a shot look like it could be in the film. The reason I don’t say “realistic,” is because realism is probably not exactly what they’re looking for. There is no such thing as realism. Realism could be the most boring thing you ever see. So they’re not looking for that. They’re looking for something that could fit in a film. You could take a concept, bring that into a 3D-generated world, or a painted matte—they want to see that you can make that transition, to take a piece of concept art and make that alive.

—EMMANUEL SHIU

Figure 3.2 Traditional painting helps develop the artistic eye. This is a fine art painting by Kim A. Dail, 3D animator.

Sculpture

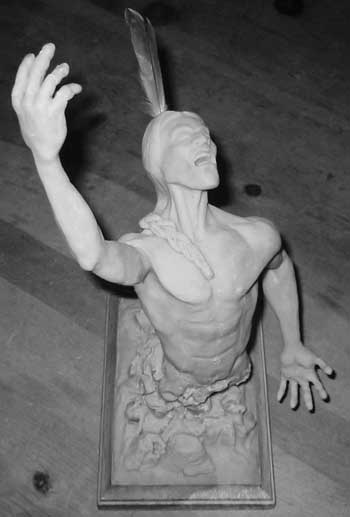

Sculpture is the closest analog in the physical world to 3D modeling and in fact, clay models, or maquettes, are often used as the basis for creating highly detailed CG models (Figure 3.3). Even if you exclusively produce artwork in the digital medium, modeling in clay can help you work out the problems in a 3D design.

Art departments in film effects studios in particular rely on clay sculptors to create lifelike models of everything from human characters to dragons. These are then scanned using laser, optical, or mechanical 3D scanners, and the resulting meshes are converted into NURBS (nonuniform rational b-splines) or some other geometry suitable for 3D animation. Related to sculpture, practical modeling—the building of architectural, industrial, or prop models—often accompanies the creation of CG versions of the same forms.

Figure 3.3 Sculpting abilities will help you understand modeling in CG. This is a maquette sculpture of a proposed CG character by Juan Gutierrez, graduate of Art Institute of California, Los Angeles.

Fashion Design

Character artists are often challenged to invent wardrobes for their virtual

characters, and nothing serves this end better than an understanding of fashion

design through the ages. If you can confidently reproduce a realistic Victorian

dressing gown, the chances are you can probably come up with a convincing cape

and collar for the Prince of Zorg. On the other hand, if your knowledge of wardrobe

is limited to hip-huggers and T-shirts, your ability to concoct interesting

wardrobes will be limited. Animators and effects artists will also benefit from

learning how fabric moves and behaves on a human form.

Created: March 27, 2003

Revised: April 9, 2004

URL: https://webreference.com/3d/cg/1

Find a programming school near you

Find a programming school near you