The Non-DesignerÂs Web Book, Third Edition

The Non-Designer's Web Book, Third Edition

Excerpted from The Non-Designer's Web Book, Third Edition by Robin Williams and John Tollett. ISBN 0321303377, Copyright © 2006. Used with the permission of Pearson Education, Inc. and Peachpit.

Frankly, type on the web can be a mess. There are so many variables as to how the type can appear in different browsers and so many limitations to what we can do. There are certain basic typographic rules web designers should adhere to and we should be as intelligent and thoughtful as possible in presenting type on web pages, but we can only go so far on our end.

If the type on your screen looks particularly terrible when you're surfing the web, it might be your own fault. Is most of the type too small? Blurry? Chunky? Letters bumping into each other? Many of these things can be fixed on the user's end, and as you fix your own screen, you'll get a clue as to the number of variables other users might be fiddling with that will affect the look of the web pages you design.

The web is all about reading information, so our goal is to make reading as easy as possible for the web page visitorÂand for ourselves on our own computers as we browse. In this chapter we'll go over the basics of good typography. We'll discuss the ways we adjust traditional typographic rules to work on the web. And we'll talk about Cascading Style Sheets (css), a technique that provides better typographic control and flexibility of design.

Readability and legibility are not the same thing. Readability refers to how easy it is to read a lot of text, extended text, pages and pages of text. In printed pages that are text heavy, a clean serif face is the most readable.

Legibility refers to how easy it is to recognize shorts bursts of text, such as headlines, buttons, signs, etc. In print and on the screen, sans serif faces are more legible. However, on the screen, some sans serif faces are even more readable because the letterforms fit into the pixels on the screen, and the missing serifs make cleaner characters.

Readability

There are a number of guidelines that can make type more readable, and a number of factors that make type less readable. You don't have total control over the type on a web page, so you need to understand what you can and can't control (read pages 250.251 regarding default font styles and sizes built into browsers). Of the things you can control, follow these guidelines:

|

Legibility

As with readability, there are general guidelines that make type more or less legible. These guidelines apply to short bursts of text, such as naviagation buttons, lists, signs, etc.

|

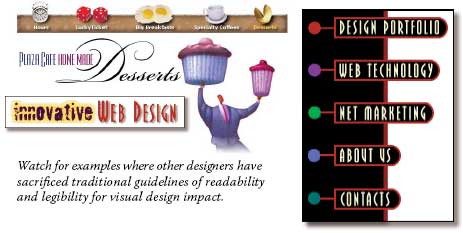

Breaking typographic rules

As with all rules, you can break them with glee. But it's best to know the rules before you break them, and then have a clear, conscious reason in wordsÂwhy you are breaking the rule and why it's okay in that case. Do it consciously and thoughtfully. Make up for it. For instance, reverse type (light type on a dark background) makes text appear smaller, but if you really want to use reverse type, compensate for it by making the type a little larger and the lines a little shorter. If you really want to set the credits in a small size, don't make them unreadable by also setting them in italic, bold, a silly face, or in a long line of text.

To create great type on a web site, it helps to be well grounded in great type in general. We suggest you read The Non-Designer's Type Book, by Robin.

Be conscious

If it looks hard to read, it is. If your page needs the designer look of a special typeface that isn't perfectly readable or legible, go ahead and use it. Just follow the guidelines to compensate for the reduced readability as much as possible. Be sensible. Don't push it so far that people will get annoyed or not spend the time to read it. Critique other pages for readability and legibility. Notice what works, what doesn't, and why.

Page text as a graphic

Some designers, in an attempt to use sophisticated typography on a web page, create a graphic of the entire page. This technique is workable, but search engines can't search the text in a graphic, and you lose the page resizing flexibility that's provided by HTML pages. And it's more time-consuming to revise or update text in a graphic than it is to update HTML text on a web page. Keep this particular technique in mind for special pages, but don't rely upon it for most pages.

Created: March 27, 2003

Revised: December 5, 2005

URL: https://webreference.com/programming/typography/1

Find a programming school near you

Find a programming school near you