HTML Utopia: Designing Without Tables Using CSS. Chapter 3: Digging Below the Surface

HTML Utopia: Chapter 3: Digging Below the Surface

-

This form of CSS offers many advantages over inline styles, but is still not as flexible or powerful as external styles (see below). I recommend you only use embedded styles when you are certain the styles you are creating will only be useful in the current page. Even then, the separation of code offered by external styles can make them a preferable option, but embedded styles can often be more convenient for quick-and-dirty, single-page work.

-

External styles: We can use a <link> tag in the head portion of any HTML document to apply a set of CSS rules in an external file to the elements of the page.

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="mystyles.css" />

The recommended method for applying CSS to HTML, external styles offer the full range of performance and productivity advantages that CSS can provide.

Using Shorthand Properties

Most property names take a single item as a value. When you define a property with a collection of related values (e.g. a list of fonts for the font-family property), the values are separated from one another by commas and, if any of the values include embedded white space or reserved characters such as colons, they may need to be enclosed in quotation marks.

In addition, there is a special set of properties called shorthand properties. Such properties let you use a single property declaration to assign values to a number of related properties. This sounds more complicated than it is.

The best-known shorthand property is font. CSS beginners are usually accustomed to defining font properties one by one:

h1 {

font-weight: bold;

font-size: 12pt;

line-height: 14pt;

font-family: Helvetica;

}

But CSS provides a shorthand property, font, that allows this same rule to be defined much more succinctly:

h1 {

font: bold 12pt/14pt Helvetica;

}

All shorthand properties are identified as such in Appendix C, CSS Property Reference.

How Inheritance Works in CSS

Before you can grasp some of the syntax and behavior of CSS rules, you need a basic understanding of the inheritance CSS uses.

Every element on an HTML page belongs to the document’s inheritance tree. The root of that tree is always the html element, even in documents that fail to include the html tag explicitly.

Commonly, the html element has only two direct descendants in the inheritance tree: head and body.

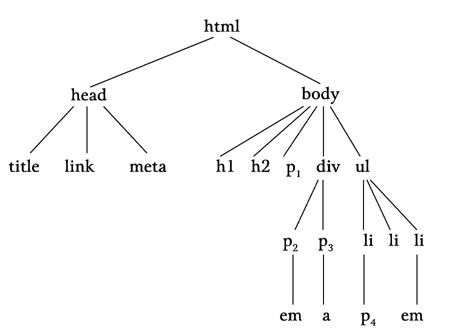

Figure 3.1 shows a simple HTML inheritance tree for a small document.

As you can see, the document has in its head the standard title and link elements, the latter of which probably links to an external style sheet. It also includes a meta element (most likely to set the document's character set).

The body consists of five elements: an h1, an h2, a p element (labeled p1 so we can refer to it easily), a div and a list (ul) element. The div element, in turn, contains two paragraph elements, one of which has an emphasis (em) element, and the other of which contains an anchor (a) element. The ul element includes three list item (li) elements, one of which includes an emphasis (em) element, while another contains a paragraph element labeled p4.

Paragraph element p1 is a direct descendant of the body.

Each element in an HTML document has a parent element (with the exception of the root html element), and is said to be a child of its parent element. In Figure 3.1, for example, p2’s parent is the div. p2 would be described as a child of the div.

Some elements in an HTML document—and most of them in a complex document—are descendants of more than one element. For example, in Figure 3.1, the paragraph element p1 is a descendant of body and html. Similarly, paragraph elements p2 and p3 are descendants of the div element, the body element, and the html element. Paragraph element p4 is tied with several other elements in the document for the most ancestors: an li, the ul, the body, and the html elements. This notion of element hierarchy is important for two reasons.

First, the proper use of some of the CSS selectors you’ll work with depends on your understanding of the document hierarchy. There is, for example, an important difference between a descendant selector and a parent-child selector. These are covered in detail in Section , “Selectors and Structure of CSS Rules”.

Second, many properties for which you don’t supply a specific value for a particular element will take on the value assigned to the parent element. This means, for example, that if you don’t explicitly define a font-family property for the h1 element in the document diagrammed in Figure 3.1, it will use the font defined in the body tag. If no explicit font-family is defined there either, then both body text and the h1 heading use the font defined by the browser as the default. In contrast, setting the width property of an element will not directly affect the width of child elements. font-family is an inherited property, width is not.

Inherited properties, properties that are inherited from ancestors by default, are indicated in Appendix C, CSS Property Reference. In addition, you can set any property to the special value inherit, to cause it to inherit the value assigned to the parent element.

This inheritance issue can be tricky to understand when you deal with fairly complex documents. It is particularly important when you’re starting with a site that’s been defined using the traditional table layout approach, in which style information is embedded in HTML tags. When a style sheet seems not to function properly, you’ll frequently find the problem lies in one of those embedded styles from which another element is inheriting a value.

Created: March 27, 2003

Revised: June 10, 2003

URL: https://webreference.com/programming/css_utopia/chap3

Find a programming school near you

Find a programming school near you