The Creative Process of Photography

The Creative Process of Photography

Excerpted from Window Seat: The Art of Digital Photography & Creative Thinking by Julieanne Kost. ISBN 00-596-10083-3, Copyright © 2006 O'Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Art of Creative Thinking

1. Master your tools.

I grew up in a household that was both creative and technical: my mother was a painter and printmaker; my father was an engineer whose hobby was photography. It was a fantastic combination of left- and right-brain pursuits.

I watched my mom draw and paint and then turn those images into beautiful, pinregistered, silkscreened works of art. At the same time, my father explored the landscape with his black-and-white photographs and converted the laundry room into a darkroom so that he could master developing and printing. While both of them honed in on their creative goals, they also developed the technical expertise to achieve them.

The first time I remember photographing with my parents, we were in a ghost town in Nevada. My mom had always taught me to look at things in my own way, and I remember the only important thing to me as I followed them through the deserted streets was making an image that was different from theirs. I'm not sure if I accomplished it, but once I had shot, developed, and printed an image for the first time, I knew I was hooked. By the time I reached junior high, I was a photographer on the yearbook staff, and my room was covered in hundreds of photographs. I was making a collage of my life on the walls.

I think the most valuable lesson I learned from my parents was that while their approaches and the techniques they used to express to themselves visually were different, they each had to master their respective tools from a creative as well as a technical standpoint in order to produce the images they wanted. Whether I like it or not, I realize that to achieve the results I'm after, I must master not only the camera, but also computers, software, printers, scannersÂa whole host of various technologies. And, needless to say, those technologies will change as fast as weather patterns over Denver.

2. Listen to what your life is trying to tell you.

Although I loved making images, I went to college at the University of California in Davis to become a psychologist. I enjoyed helping people who were at a disadvantage and who might prosper if only they had the information that they needed to make a change. I was also a highly competitive college athlete, so I supplemented my major in psychology with a minor in sports therapy.

In retrospect, it was a great contrast: the unquantifiable study of the human mind combined with the far more literal study of biomechanics. However, an understanding of the way the body behaves and the physical stress it can take didn't prevent me from injuring myself. I broke my foot the first year, shattered my wrist the second, and fractured a rib the fourth.

After being injured three out of the four seasons of my college career, I started to wonder whether sports therapy was the right choice for me. Certainly I had been through enough physical mending to have the necessary experience, but at the same time I was extremely disappointed at having been unable to compete. So, although I graduated with a B.S. in psychology, it was quite unclear to me what I was going to do after college.

Instead of returning to school to become a doctor of psychology, I attempted to persuade my parents to shift gears and send me to photography school instead. They didn't take the bait (and even to this day, I can't say that I blame them!). Although I could have pursued a higher degree in psychology, I wanted to find a way to help people while pursuing what I was interested in: photography.

Ultimately, I took six months off and went to work in a one-hour photo store while taking courses in photography at a local community college. In 1991, I was hired as a photo technician at a medical imaging company. There I captured images off Betacam video tapes and removed color casts, noise, and patient names from ultrasound images. At the same time, I completed an associate's degree in art at Foothill College, where I studied with Stephen Johnson, an internationally recognized photographer and pioneer in the field of digital photography.

When we met, Stephen was working closely with Adobe, giving feedback to the Photoshop development team about their product. Through that connection, I was recruited by Adobe in 1992 to serve on the technical support team for Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Premiere. When Adobe acquired Aldus in 1994, my role changed and I became a graphic designer in the techni technical publications group, working on the Classroom in a Book series, "Beyond the Basics" tutorials, and the user guides for Photoshop, Premiere, and Illustrator.

3. Be open to whatever comes your way.

In 1998, a twist of fate put me on a stage for the first time. Fellow Adobe employee and mentor Luanne Cohen asked me to speak in her place on "What's New in Photoshop 5.0" at the HOW Design Conference. At first, I was absolutely terrified, but I quickly realized that the people in the audience weren't really watching meÂthey were watching the screen. What they wanted to know was something I knew inside and out, and all I had to do was relay that information to them as clearly as possible.

As I did the demo, I saw light bulbs going on in the minds of the audience. It was so inspiring. What surprised me was that it wasn't even the most advanced feature that elicited the biggest response from the audienceÂinstead, it was the simple tip they'd never heard before that could help them work more efficiently every single day. I realized that day that Photoshop training was what I wanted to do.

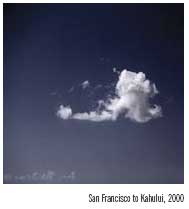

I'm certainly not the only person who has ever snapped a photo out the window of a plane. From a practical standpoint, however, many people have a difficult time shooting decent photos this way. If you take an average point-and-shoot film camera and aim it out the window, you are pretty much guaranteed to get a washed-out image with reflections, lens flare, and an in-focus window and an out-of-focus cloud. Likewise, when the sun is setting and those wonderful pastel colors envelope you, it's probably dark enough that the flash will automatically trigger, leaving you surprised and definitely disappointed by the results. These are only a few of the difficulties of photographing through a plane window.

The events of 9/11 have had a profound effect on the process, making capturing images even more difficult. There was a time when I could huddle against the window with a black sweater over my head to hide reflections from the glass, but now I'm hesitant to do anything that looks suspicious. The flight attendants have even asked me to turn off my camera: "Anything with an on/off button must now be turned off." Then there's the grilling process that takes place before boarding a plane. It's not as bad with digital cameras as it is with film, since digital images obviously run a lower risk of being ruined by an x-ray device, but with all of the electronic equipment I carry, I fully expect to be pulled aside so that security can give my camera bag and computer the "digital sniff test."

It's interesting to me that none of my fellow passengers has ever asked me what I'm doing when I shoot photos out the window. I'm not sure if they think it's a waste of time (because they've tried it and their images didn't turn out well), if they're afraid to ask, if taking photographs comes across as a personal activity that wards off social interaction (like wearing headphones), or if they think it's simply my first time on a plane and I'm giddy about the experience.

Regardless, I love knowing that what they see and what I'm capturing are often completely different things.

Created: March 27, 2003

Revised: April 10, 2006

URL: https://webreference.com/graphics/channels/1

Find a programming school near you

Find a programming school near you