WebReference.com - Part 1 of Chapter 3: Professional XML Web Services, from Wrox Press Ltd (2/7)

[previous] [next] |

Professional XML Web Services

The SOAP Message Exchange Model

The SOAP specification defines a model for exchanging messages. It relies on three basic concepts: messages are XML documents, they travel from a sender to a receiver, and receivers can be chained together. Working with just these three concepts, it is possible to build sophisticated systems that rely on SOAP.

XML Documents As Messages

The most fundamental concept of the SOAP model is the use of XML documents as messages. SOAP messages are XML. This provides several advantages over other messaging protocols. XML messages can be composed and read by a developer with a text editor, so it makes the debugging process much more simple than that of a complex binary protocol. As XML has achieved such widespread acceptance, there are tools to help us work with XML on most platforms.

We won't examine a SOAP message in detail until later in the chapter, but here is an example of one:

<soap:Envelope xmlns:soap="https://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/"

soap:encodingStyle="https://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap

/encoding/">

<soap:Body>

<w:Greeting xmlns:w="https://www.wrox.com/helloworld/">

<w:message>Hello world!</w:message>

</w:Greeting>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>Senders and Receivers

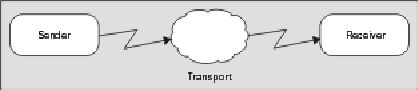

When SOAP messages are exchanged, there are two parties involved: a sender, and a receiver. The message moves from the sender to the receiver. This operation is the basic building block of SOAP message exchanges, the smallest unit of work. The figure below illustrates this simple operation:

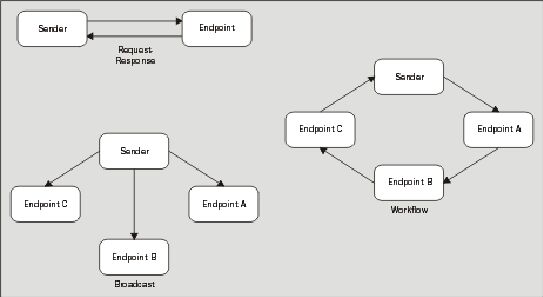

In many cases, however, this type of operation is not enough. A more common requirement would be for messages to be exchanged in request-response pairs. As we will see later in the chapter, this is the method SOAP uses with the HTTP transport and/or the RPC convention. Requiring that model, however, would make it difficult to design one-way message exchanges. By starting with the most basic operation, a one-way message exchange from sender to receiver, more complicated exchanges can be composed without preventing the simplest exchanges from occurring. This gives us the ability to construct message chains.

Message Chains

SOAP messages do not have to follow a traditional client-server model. Messages might be exchanged in this manner, as in the case of HTTP, or a chain of logical entities might process the messages. This concept of a logical entity that performs some processing of a SOAP message is referred to as an endpoint. Endpoints are receivers of SOAP messages. It is the responsibility of an endpoint to examine a message and remove the part that was addressed to that endpoint for processing.

It is worth mentioning here that despite the "O" in SOAP, there is nothing object-oriented about the SOAP model. Endpoints, as well as clients, can be written in any language, and there is no presumption of "objects" existing on either end of the wire.

As the model allows us to combine one-way messages into more complex operations, endpoints can function as both receiver and sender. This capability allows for a processing chain to be created, with messages being routed through the chain with some potential processing occurring at each step. Endpoints that function as both sender and receiver, passing messages that they receive on to another endpoint, are referred to as intermediaries. Intermediaries and the message chain concept allow developers the opportunity to construct sophisticated systems based on SOAP. The figures below show some examples of message patterns that can be achieved through chaining endpoints together:

Endpoint Behavior

Thinking of SOAP in terms of endpoints helps to understand the flexibility of SOAP messaging. No matter what route a message takes, or how many endpoints may process it, all endpoints must handle messages in a certain way. Here are the three steps that an endpoint must take to conform to the specification:

- Examine the SOAP message to see if it contains any information addressed to this endpoint

- Determine which of the parts addressed to this endpoint are mandatory, if any. If the endpoint can handle those mandatory parts, process the message. If not, reject it

- If this endpoint is an intermediary, then remove all the parts identified in the first step before sending the message to the next endpoint

We will revisit these steps later in the chapter. By conforming to these three requirements, endpoints can be chained together to form complex systems.

Modular Design

SOAP is open and extensible. That means that all of the following scenarios are acceptable and allowed by the SOAP specification:

- A desktop application composes a SOAP message that requests stock quotes and sends it as the body of an HTTP POST. A web server receives the POST, processes the message, and returns a SOAP message in the HTTP response

- A server process composes a SOAP message that describes a system event and broadcasts the message over named pipes to other servers on the network

- A software developer with limited social skills decides to compose a SOAP message declaring his love for a co-worker and sends it as an e-mail attachment (this is likely to be a one-way message)

How is it that SOAP can support such different scenarios with the same model? The answer is in SOAP's modular design. Throughout the specification, there are placeholders left open for future extensibility of the protocol. SOAP is designed to be extensible in all of the following areas:

- Message Syntax  the SOAP message format does have an area set aside for extensions to be added (we will examine this area, the

Headerelement, in the next section) - Data  the SOAP payload can contain any type of data. SOAP provides one method for serializing data, but applications can define their own rules as well

- Transport  SOAP does not dictate how messages will be transported during the exchange. SOAP defines how messages should be exchanged over HTTP, but any communications protocol or method can be substituted for HTTP

- Purpose  SOAP does not define what you want to put into a message. Although this may sound like we are counting data twice, there is a difference between data and purpose, as we will see later in the chapter

Extensibility is important, but without some concrete implementations of these concepts, SOAP would be just a lot of interesting concepts. Luckily, the authors of SOAP provided a description of one implementation each of: data, transport, and purpose. For data, the Specification provides the SOAP encoding rules (section 5 encoding). For Transport, a transport binding for HTTP is defined. Finally, for purpose, the specification defines a convention for using SOAP messages for RPC.

We will cover each of these topics in more detail in this chapter. It is important to remember these four concepts, because the fact that they are separate from the protocol and therefore extensible is one of the biggest advantages of SOAP.

[previous] [next] |

Created: November 12, 2001

Revised: November 12, 2001

URL: https://webreference.com/authoring/languages/xml/webservices/chap3/1/2.html

Find a programming school near you

Find a programming school near you